Laméca file

Afro-Colombian music

4. ARRULLO, A LULLABY FOR THE SAINTS

Religious life in the southern Pacific revolves around the Catholic saints, as well as the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, who provide protection and help to the people who take them on as patrons. Like the deities of the Gold Coast and Bight of Benin areas of Africa which they supplanted in the lives of the mine slaves of the 18th century, the saints are notoriously capricious, and they must constantly be wheedled or appeased, often by appealing to their vanity and desire for attention. The arrullo ceremony, a word meaning “lullaby” is held to appease a saint, often in conjunction with a favor being asked or for which a saint is being thanked, or to commemorate a saint’s feast day.

Course of the arrullo

The arrullo takes place at the sponsor’s home, where an image of the saint is placed on an altar in the main sitting room. Sometime after dusk, the participants form two lines in the center of the room, making a kind of corridor leading to the altar. The ceremony begins with spoken Catholic prayers, joined in the appropriate places by the others present. Then the music begins, presided over by the cantadoras, alternating with more prayers. The music played is primarily the genre called juga, alongside the occasional bunde (treated in the next section).

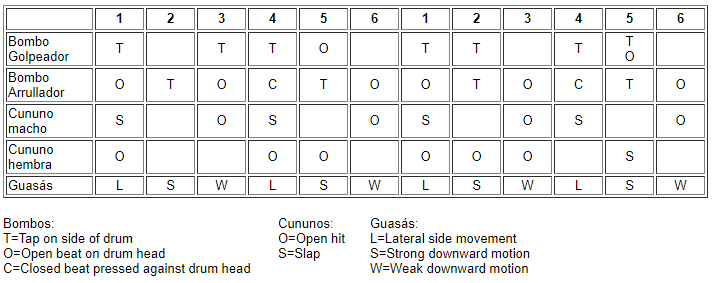

The jugas usually do not include a marimba, but the percussion parts for the various instruments are very similar to that of the various kinds of music played in the currulao dances.

Below is a transcription of some of the more basic of those patterns :

At specific moments in the arrullo, female worshippers dance toward the altar between the two lines to declaim religious poems called loas to the saint. Later, men are invited to do the same. The music, prayers and loas alternate with one another, and periodically the hosts pass trays of coffee, liquor, and cigarettes among the participants. In some places, arrullos end with specific songs, each with their own particular choreographies: “La bámbara negra,” “El caracumbé,” “Los cuatro doctores,” and “Redentor del mundo.”

When the arrullo is concluded, those present may continue to drink and dance secular jugas or guitar music until dawn. If a marimba is present, the gathering may become a currulao dance.

Epifanía (San José de Timbiquí)

Heat and joy

The saint is most pleased by a joyful arrullo, one which is seen as generating calor (heat). This heat makes the saint happy by counteracting the chill of the divine sphere, reminding the saint of when he was human, simultaneously appeasing him, giving him power, and bringing him closer to the world of human affairs. This humanization of the saints is reiterated in the lyrics of the jugas, which depict them in mundane, human contexts :

María lavando - Mary washing

José tendiendo - Joseph hanging [the laundry]

O, el Niño llorando - O, the Child crying

Que sol que está haciendo - From the hot sun

This human-ness, manifested by human “heat” (calor), is generated in a number of ways, not least among them, by a generously boisterous atmosphere - all the participants joke with one another, encouraging or gently poking fun at one another. They are aided in this joyfulness by drinking alcohol, which in itself generates heat and facilitates both music-making and worship.

The act of playing music is itself perhaps most important in generating heat as energy builds in the hands of the drummers and the voices of the cantadoras. As the musicians play with more intensity, the participants become more boisterous, and the saint itself becomes happier, heat is generated and sent between the various participants (including the saint), accumulating at each node. (See Losonczy 2007).

Epiphany Day (San José de Timbiquí, 2006).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

Balsada

Before or after the arrullo, the saint’s image may be paraded through the town’s streets to the accompaniment of jugas and bundes and the sound of firecrackers. A very particular kind of procession is the balsada (from the word balsa, raft), essentially an aquatic version of the procession. Given the scarcity of both religious statues and priests, a particularly popular local saint may be taken from village to village by a small group of lay authorities along a river so that it may be worshipped with arrullos by the local population around the time of its feast day.

The villagers lash canoes together side by side, and cover them with boards to form a floor, then building a kind of pavilion as a second floor, and sometimes even more levels, giving it the appearance of a multistory wedding cake. Each level may have a different musical group, playing and singing the jugas and bundes that please that saint.

In a settlement downriver, the villagers await the balsada, lighting firecrackers and playing music. As the balsada draws closer, children light small candles which are fixed in coconut shells and place them in the water. The candles outline the curves of the river in light as they float downstream in the hundreds. As, finally, the anticipated balsada emerges from around a bend upriver, its appearance is greeted by more energy from the musicians, more firecrackers, more shouts of joy. Finally, the raft arrives, and the saint gently carried off in a procession that will carry it to the next arrullo.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. Black Colombia

2. The Southern Pacific

3. Currulao, the marimba dance

4. Arrullo, a lullaby for the Saints

5. Alabados and Chigualo, music for the dead

6. Black Pacific modernities

Musical illustrations

Sources

______________________________________

by Dr Michael Birenbaum Quintero

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Général de la Guadeloupe, 2009-2016