Laméca file

Cuban Abakuá music

1. THE ABAKUÁ INSTITUTION : A CARABALÍ FOUNDATION IN CUBAN SOCIETY

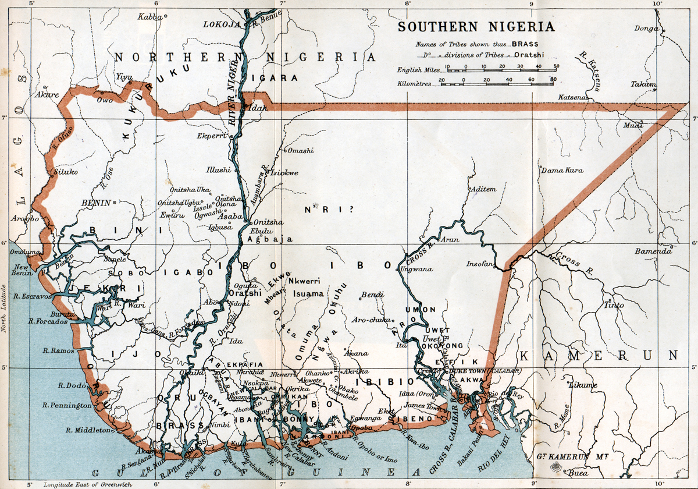

Abakuá is a mutual-aid institution with initiation rites that was created in colonial Cuba by forced-migrants from the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon. Despite centuries of adaptation to the Cuban context, the Abakuá system remains best understood in relation to its African sources, of which the Cross River Ékpè ‘leopard’ society was a primary model.

Leonard (1906), map of Nigeria and Cameroon.

For centuries, Ékpè played several major roles in the Cross River region. It conferred full citizenship rights regardless of personal origin. Depending on the level of title attained, it accorded enhanced political status in one’s community, and its sumptuary costume evoked the type of reverence accorded to the ‘toga virilis’ in ancient Rome. Ékpè also served as the no-nonsense community police, with powers to discipline lawbreakers and even confiscate their property. Ékpè created rich entertainments comprising intricate dances, songs and body-mask performances by members. Finally, Ékpè was a school for esoteric teachings regarding human life as a cyclic process of regeneration including eventual reincarnation (cf. Bassey 1998/2001; Miller & Ojong 2012).

From the 1640s through the 1840s, the main coastal port of the Cross River region — today known as Calabar, Nigeria — was an embarking point for the Atlantic slave trade.

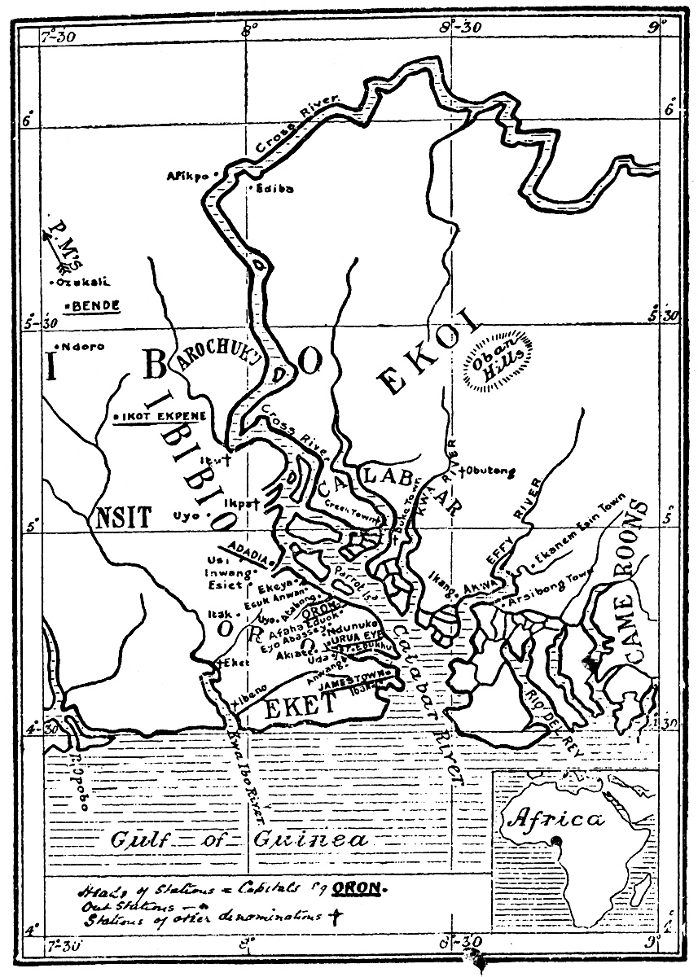

Ward (1911), map of Calabar region, Nigeria.

People forcibly migrated from there to the Caribbean and Americas were known as ‘Carabalí’ (reversing the ‘l’ and the ‘r’) after this port, which was known as ‘Old Calabar’ from the 17th to the early 20th centuries. Being among the most linguistically diverse regions of Africa, migrants from the Cross River region were rarely identified by tribal affiliations, which were numerous and uncertain, but instead by their point of departure.

Carabalí peoples were exported throughout the Americas. The strongest case for the collective transmission of their cultural institutions, however, occurred in the port city of Havana, Cuba, with the foundation of the Abakuá mutual-aid institution in the early 1800s. This level of self-organization was enabled because in urban centers throughout the Portuguese and Spanish American colonies, African migrants organized ‘cabildos’ — also called ‘nation-groups’ — associations that included migrants of similar regions and language groups for purposes of mutual-aid. In the 1750s in Havana Cuba, five ‘Carabalí’ cabildos were documented, while others were created in the nearby port city of Matanzas. Certainly knowledgeable members of Ékpè institution born in Africa were cabildo leaders in Cuba. But because the cabildos were for those born in Africa, ‘Carabalí’ leaders eventually created Abakuá lodges for their own children. Given the extremely difficult context of existing within a slave society, the first Abakuá lodges functioned as part of an underground network of anti-colonial activity.

So far, the earliest references to Abakuá activity emerged in the 1812 Aponte ‘Conspiracy’, the first anti-colonial and abolitionist movement in Cuba, organized in Havana by Lucumí descendant José Antonio Aponte. This multi-ethnic movement ended in the execution of its leaders by Spanish authorities, and the suppression of its documents for 150 years, until their declassification in 1963 (Cf. Pavez 2006). While the first Abakua lodge is generally agreed to have been founded in 1836, recent evidence suggest that Abakuá may have been organized decades earlier, during the Aponte movement, but was suppressed until the 1830s. Nevertheless the first lodge was called Efik Ebuton, after the Efik-speaking community in Calabar called Obutong. Since its foundations therefore, Abakuá had political functions within the colony, as well as spiritual functions for Calabari-descendants to memorialize their African sources and philosophies. By the 1840s (if not earlier) other Abakuá lodges established in Havana were named Eforisún Efó, named after an Efut (Balondo) community in Calabar, and Orú Ápapa, likely named after the Úrúán communities of the Calabar region. With these lodges the three Abakuá lineages were established; they continue to exist into the present: Efí (Efik), Efó (Efut), and Orú (Úrúrán).

Like other organizations created by Africans in the colonial period, Abakuá was suppressed by the authorities, especially during crisis periods like in 1844, known as ‘the year of the lash’, when authorities tortured and killed many Cubans suspected of participating in another anti-colonial movement. The persecution of Abakuá was intended to lead to its extinction, but in 1863 one Abakuá leader and his supporters strategically created a lodge for white Cubans, who happened to be the sons of illustrious and powerful families in the colonial government. Andrés Petit (a.k.a. Andrés Valdés Petit Cristo de los Dolores), a title-holder of the lodge Bakokó Efó in Havana, founded the first lodge of white men. The whites wanted to belong because Abakuá was exciting, and it was also emerging as a symbol of Cuban identity. Petit envisioned that the whites would help defend the Abakuá society against persecution. This lodge, called Mukarará Efó (white men of Efó), went on to create many others, in effect creating a fourth Abakuá lineage which also continues into the present. In the same decade (1862), Abakuá lodges were founded in the port city of Matanzas. In the early 20th century, Abakuá lodges from Matanzas migrated to the nearly port city of Cárdenas, while others were founded there.

At present in the port cities of northwestern Cuba: Havana, Matanzas and Cárdenas, there exist over 150 lodges with more than 20,000 members. Abakuá ritual activities are exclusive to these three ports cities. Because of its African heritage, as well as its history of resistance to authorities, for many in Cuba’s dominant classes, Abakuá remains a symbol of ‘backwardsness’, of marginality and even criminality. Nevertheless for many Abakuá members and their communities, Abakuá is a symbol of the Cuban nation itself, being founded much earlier than the nation (1902), and being a deep psychological marker for Cuban resistance to enslavement and subjugation. In short, Abakuá is part of a pan-Caribbean ‘cimarrón’ culture. Abakuá has never been supported officially in Cuba, but has received greater or lesser levels of acceptance in various periods of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Although Abakuá is popularly known as a ‘religion’ by its members, it is more accurately described as a prestige club for a privileged few who were selected for membership. Even amongst the overall membership, only a few lodge leaders have access to the inner mechanics of the institution, which were taught by the African founders to their Cuban children in the 1800s. In the contemporary barrios of Havana, Matanzas and Cárdenas, Abakuá leaders report that out of 10 young men, all want to become Abakuá members, but only about three are selected as eligible. This is because Abakuá have historically investigated and screened potential members for moral qualities, interviewing their families (especially their mothers) and their larger communities about their conduct. Those with anti-social behavior were not allowed. And those members who did not behave well were also sanctioned or expelled.

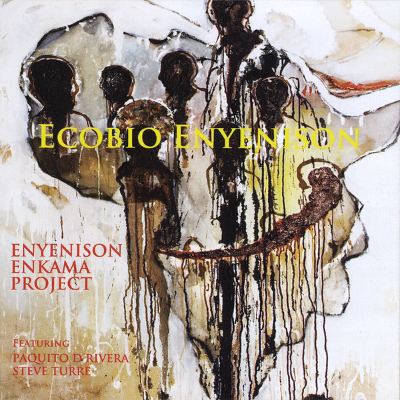

In the 21st century, with new possibilities of communication and travel, Abakuá members have been able to communicate with their counterparts in Calabar, leading to an unprecedented reexamination of the African sources of Abakua history and practice, as well as the role of Ékpè and Abakuá in the trans-Atlantic Cross River region diaspora. In 2007 in Calabar, Nigeria an association of Ékpè lodges from various tribes was created, Calabar Mgbè, as an expression of the shared practice of Ékpè historically in the region. At the invitation of the Musée Quai Branly in Paris, members of Calabar Mgbè were invited to perform with Cuban Abakuá members for four days on stage, in an exploration of their shared traditions (1). As a result, in 2009 three of the Cuban participants released a CD recording of music with Abakua and Ékpè content reflecting their happiness with the trans-Atlantic dialogue (2). Called “Ecobio Enyenisón” (interpreted as ‘Our African Brothers’ in Abakuá), this recording fused Abakuá and Ékpè ritual phrases within a vanguard Caribbean-jazz context.

The first track “Eribó Eribonyé” is an homage to the Eribó drum that represents the mythic female founder of the society in Africa centuries ago. The conch shell is blown to symbolize the maroon (cimarrón) rebel traditions of the Caribbean. This composition is a fusion of Abakuá music with jazz elements (in the bass and trumpet). The bell pattern of the Cuban son is heard in the ‘march’. This recording has three lead voices: Angel Guerrero, Román Díaz, and Pedrito Martínez. The two ‘cherekawa’ maracas (or ‘erikunde’) are played in the style of Calabar Ékpè.

"Eribó Eribonyé" (extract) by Enyenison Enkama Project - album Ecobio Enyenisón (Habana Harlem, 2009).

Also in 2009, the author created “Calabar Mgbè” International Review in Spanish, each volume containing four pages of photographs and text intended to bring information about the African heritage of Abakuá. Issues are posted at :

http://www.afrocubaweb.com/abakwa/revistacalabarmgbe.htm

_________________________________

(1) Information about this event in Paris is found at : http://www.afrocubaweb.com/abakwa/calabarmgbe.htm

(2) ‘Román’ Díaz, Angel Guerrero-Vecino, and ‘Pedrito’ Martínez.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. The Abakuá institution : a Carabalí foundation in Cuban society

2. Styles of Abakuá music : Nyánkue rites; Efó and Efí lineages; the lamellophone; percussion instruments

3. Abakuá ceremonial music

4. Abakuá influence in Cuban popular music

Musical examples

Glossary

Sources

______________________________________

By Dr Ivor L. Miller

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Départemental de la Guadeloupe, 2016