Dossier Laméca

VODOU MUSIC IN HAITI

4. THE KONGO/PETWO ROOM

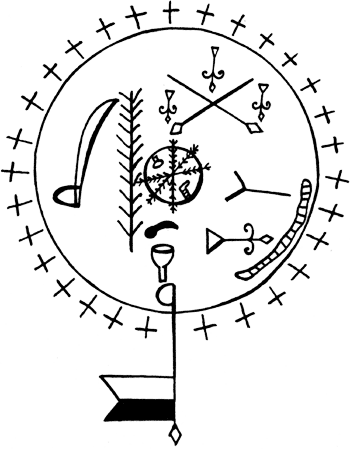

Vèvè for Simbi.

In the years just before the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) a majority of the African-born slaves came from the Congo Coast, and their spiritual beliefs and customs enriched and complemented those of Guinea Coast Africans. As Vodou uses the word Rada to name the Guinea branch, it uses “Petwo” for the Congo branch. Scholars have offered several theories for the origin of the word Petwo, but it seems to recall one or more slaves who, like a series of Congo kings, took the name Pedro and the honorary title Don from Portuguese colonists. Moreau de Saint-Méry, a white Creole who exhaustively documented St. Domingue, reported a “Don Pedro dance” in the southern peninsula in the 1760s, a dance of violent trembling to explosions of gunpowder. French authorities banned the dance for its spirit of sedition.

We find the Kongo/Petwo Room on the left end of the spiritual spectrum of Vodou. The pole accommodates spirits of great heat and turbulence, who favor the color red and the element of fire. Highly aggressive, they can bring about radical change, including revolution. Many of these spirits bear European or Guinea Coast names: Marinette, Kalfou (Carrefour), Èzili Dantò, Danbala La Flambeau, Jean Petwo (from Don Pedro). This has led some researchers to conclude that they are entirely Creole (born in the colony), but others can identify characteristics in these lwa that recall spirits from the Congo region.

The Petwo altar.

UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Photo by Dennis Nervig.

To the right of the fire spirits one finds others with specifically Kongo names who dwell in rivers and forests. Simbi Makaya (Simbi of the Leaves in kikongo) typifies Kongo healing arts and the exquisitely decorated medicine packets called pakèt kongo.

"Petwo" (1992) by master drummer Frisner Augustin (extract).

Contemporary Haitians perform two types of dance from the Congo, and each differs considerably in temperament. The volatile dance petwo clearly evolved from the Don Pedro dance described by Moreau in the eighteenth century. The fundamental step demands the coordination of the torso, which literally trembles, and a basic foot pattern that begins with a step backward in anticipation of the main pulse. The dances kita and boumba (both kikongo words) are varieties of the dance petwo, the former executed at an extremely rapid pace and the latter more slowly. The seductive dance kongo, the second major type from the Congo coast, includes several varieties. Kongo fran and kongo payèt appear almost exclusively in performance today, both in the temple and the theater. The basic kongo fran step combines a gentle rotation of the hips, a toe-heel foot movement, and a swirling of the skirt of the female dancer. Kongo payèt uses a similar rotation of the hips, but feet are placed flat and parallel on the ground.

"Kongo payèt" (1992) by master drummer Frisner Augustin (extract).

"Swa Kongo" (2004) by La Troupe Makandal (extract).

This traditional Petwo drum uses a goatskin head attached to a conical softwood body by means of cords interlaced in tourniquet style, similar to drums found in the Congo. One slides the side clasps, called ralba, up or down to tune the head.

Music instruments and hand technique characterize the Petwo and Kongo spirits and invite them to reveal themselves in possession. The bodies of Petwo drums are softwood, conically carved and covered at the upper opening with goatskin. A hoop holds the head in place. Cords lace around the hoop and anchor to the lower end of the body by means of another hoop, holes, or knotting methods. Pegs applied to the lacing control head tension. The Kongo timbal, from the french word for kettledrum, is rather a softwood cylinder a quarter of a meter long (and therefore called ka in some places), covered at both ends with goatskin held in place with hoops and lacing. Drummers play Petwo drums with bare hands and the timbal with a pair of slim sticks for a sharp sound. One notes that some Petwo drum patterns favor a hand stroke that resembles the crack of a whip, perhaps to echo the priest’s cracking of the whip against the floor of the temple. The sounds of whistle and whip enrich the sonic texture and appropriate slave-era tools of oppression. The Petwo rattle takes the nickname of the flamboyant tree—tchatcha—for the sound made by the seeds of its fruit when excited by the wind.

The master drummer plays the Petwo drum with hands only. Here, he strikes a bass tone in the center of the head, then a high ringing tone on the rim.

The structures of rhythm and song likewise mark the character of the Petwo and Kongo lwa. Every rhythm played for these spirits features the kata pattern, whose strokes segment the measure in 3:3:2 ratio. One may hear it in a variety of drum and percussion parts, from the staccato of the timbal to the clatter of the tchatcha. The kata plays against a steady pulse (1:1 ratio) rendering the offbeat feel for which black music is known, in and out of Africa. A similar sense of play inspires song. The “sender” of a song is not necessarily a specialist, as in Rada rites, and more than one person may take up the lead during a set. Kongo/Petwo sets often seem to concatenate endlessly, in contrast to the Rada habit of three slow songs followed by a fast one.

Vèvè for Kongo Wangol.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. Backdrop

2. The musicians of Vodou

3. The Guinea room

4. The Kongo/Petwo room

5. Work and celebrate: konbit, carnival, and rara

6. Vodou music in neo-traditional contexts: folklore and roots music

Bibliography / Discography

Musical examples

______________________________________

by Dr Lois Wilcken

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Général de la Guadeloupe, 2005