SUMMARY

1- A Panorama of Dominican Folk Religion and its Music

2- Afro-Dominican Religious Brotherhoods and their Palos Music

3- Case Study of an Afro-Dominican Cofradía: The Brotherhood of St. John the Baptist of Baní and its "Sarandunga"

4- The Dominican Saint's Festival and its Music

5- The Drum Dance [Baile de Palos]

6- Transnational Dominican Palos Music

Musical examples

Sources

2. Afro-Dominican Religious Brotherhoods and their Palos Music

Location of current main cofradías on political map of Dominican Republic.

The Dominican long-drums (palos or atabales) are associated with Afro-Dominican religious brotherhoods (cofradías) as the voice of their patron saints. The Dominican cofradías are derived from the medieval Mediterranean phenomenon of guild-based societies, each associated with a parish. They were also established by Africans present in southern Spain since at least a hundred years before the conquest of America. These Christianized Africans, called ladinos, were the first Africans to be brought to the colony of Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola, arriving by about 1502.

The Spanish cofradía is comprised solely of males with rotating leadership positions. In Spain itself or Santo Domingo that structure was reinterpreted such that the leadership became mainly female and the positions lifelong and inherited, as a family lineage whose patron saint is the family totem. The Africans' cofadía was replicated elsewhere in the Spanish and Portuguese Afro-Latin American cultural area and came to include the cofrarias of colonial coastal Brazil, the Cuban cabildos, and similar organizations in Venezuela, Panama, and Peru, and other sites. The cofradía became a major institution of indigenous America as well, adapted to Native-American folk Catholicism, particularly in Mexico and Central America.

In Afro-Latin America, the cofradía served as a mutual aid society. This included its important function as a burial society given the pan-African concept of the ancestors as elders and consequent importance of the dead. Following the abolition of slavery, thecofradía has virtually died out virtually everywhere because this social sector has had increasing access to social services. The exception is in the Dominican Republic, where we can observe a living remnant of colonial society.

Directors of the cofradía of the Holy Spirit in Cotuí (designated with sashes), with the banner and the palos of the brotherhood.

Each cofradía is locally based, and located mainly in regions with notable African influence (Central-South, Southwest, East, and Eastern Cibao [north], in that order of importance). The most important cofradías today are in San Juan de la Maguana, Villa Mella, Baní, and Cotuí, with smaller ones in Los Morenos in Villa Mella, Santa María in San Cristóbal, Las Matas de Farfán, Elías Piña, Los Cacaos in Samaná (a family originally from the east), Arroyo Salado in Peravia, and undoubtedly elsewhere. Others have died out; is said that there used to be a large cofradía to the Holy Cross in El Seybo. Since cofradías are locally- and family-based, one cofradía may have no knowledge of the others. Yet all are similar in structure and function, including largely female leadership, the use of the palos (or other drums), and the types of their ritual activities, namely celebrations of their patron saint and death rituals of their members.

Image of the Holy Spirit (as a child doll like St. John the Baptist - see chapter 3) at the cofradía in Santa María, San Cristobal.

With regard to the patron saint of the cofradías, in the eighteenth century, the most common patron saint of Afro-Dominican cofradías appears to have been St. John the Baptist [see chapter 3], largely substituted in the nineteenth century by the Holy Spirit. However, the icon used for St. John, a doll figure (St. John as a child) dressed in red and white, has also been taken to represent the Holy Spirit, suggesting intra-African syncretism among Africans of changing ethnic origins. This phenomenon is undoubtedly replicated in other aspects of Afro-Dominican folk religion such as its music. In addition to written sources, icons, rituals, instrumental types and musical styles, and the non-Spanish words in some sung texts provide clues to a largely unwritten past of the cofradías.

The Afro-Dominican cofradías vary with the relative emphasis given to events for the saint or for the dead, how either is celebrated, and the specific death rituals emphasized. Those brotherhoods dedicated to the Holy Spirit may celebrate on the Fridays of “Small Lent” (Cuaresma Chiquita), the seven-week period between Easter and Pentecost, i.e., the day of the Holy Spirit. The brotherhood of the Holy Spirit in Villa Mella, a special enclave which plays a type of palos called the “congos,” is the brotherhood most dedicated to death rituals of their members, emphasizing the ninth night of the novena following burial, called the "rezo," which serves as a “second burial”--of the spritual remains, as it were; and the anniversary of death or "banco."

The cofradías also vary with regard to the musical ensemble, the structure of its palos drums and the musical genres, rhythms, and texts. However, all Dominican palos are hollowed-out logs (hence the term “palos,” which means “trees”), are played with the hands, and the master drum is the larger and wider one.

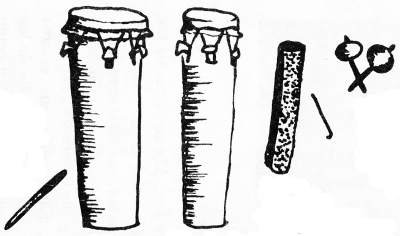

Palos type and ensemble of the east. In the northeast, three güirasare used and no maracas, rather a small stick that beats the body of the master drum. In Monte Plata (the western border of this region): one güira and a pair of maracas.

Audio 1 - "Palo corrido East" (M. E. Davis, 1973)

Palo corrido of the type from the East (El Seybo).

In the northeast, the palos ensemble is comprised of a set of two drums: palo mayor (“master drum”) and alcahuete (literally, “pimp”), with single cowhide heads attached with hoops and pegs. The palos are accompanied by one to three güiras (metal scrapers) and a little stick beaten on the body of the palo mayor generally called “catá” (“strike”). The rhythms played are “palo corrido” (“running,” probably in reference to its fast tempo), the more modern and less sacred "palo aguarachado" (at least in Bayaguana) and the lugubrious “palos de muerto” (“drums of the dead”). In the western part of this region, Monte Plata, the instruments are eastern but the rhythms are of the central-south region; here, gourd shakers also called maracas are added. In the northwestern part of this region which lies in the eastern Cibao (northern valley), Cotuí y Cevicos, the pegs are very tiny.

Palos type and ensemble of the east; example from Monte Plata.

Audio 2 - "Palo abajo Peravia" (M. E. Davis, 1973)

Palo abajo from the historical region of the "Savannah of the Holy Spirit" (central-south) (El Limonal, Peravia).

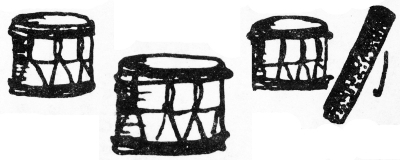

In the central-south, the ensemble is a set of three very narrow drums with single cowhide heads: the palo mayor positioned between two alcahuetes, with perhaps one güira. The southern palos are virtually identical to the Central African (Bantu) ngomadrums, as are the yuka drums of Cuba, although the music is different, because instruments and musical style are not covariables. The central-south ensembles play the "palo abajo" and "palo arriba" traditionally associated with the dead; the two rhythms are usually adjoined into a single piece, however, in the enclave of Los Morenos in Villa Mella (Province of Santo Domingo Norte), they are separate pieces. In the cofradía of Santa María in San Cristóbal, there are even more rhythms, including seis and tarana. In this northern part of San Cristóbal province, there is in fact quite a lot of variety among the communities. In Doña Ana, a faster rhythm is called "atabales." In this central-south region the palos may be nicknamed "canutos" or "cañutos."

Performance of central-south palos by the cofradía of the Holy Spirit in Santa María, San Cristóbal.

In the interior southwest, the ensemble is similar, but the drums are much wider and the second alcahuete, called "chivita," is shorter, and no güira is used. The main rhythm is "palo corrido" or "palos del Espíritu Santo" ("drums of the Holy Spirit") in reference to the largest cofradía in the country, whose seat is in the rural community of El Batey.

Palos variant: The congos of the cofradía of the Holy Spirit in Villa Mella (Santo Domingo Norte Province) : congo mayor, alcahuete, canoíta, and single maracas played by women who sing the chorus in the songs.

Congos performance by grandchildren of the late Sixto Miniel, "capitán" (head of the congos ensemble) of the cofradía of the Holy Spirit. Mata los Indios, Villa Mella.

Audio 3 - "Congos calunga" (M. E. Davis, 1973)

Congos of Villa Mella: their most sacred piece, "Calunga".

The large cofradía of Villa Mella, of the Holy Spirit, is an Afro-Dominican enclave with special instruments : the "congos," which have their own repertoire of twenty-one pieces. They are comprised of two drums with double heads of laced goatskin, the alcahuete a third the size of the "congo mayor." The idiophones include the unique "canoíta," a sort of clave in which one of the two pieces is hollowed out like a little canoe. Single maracas are played by women who sing the response. This brotherhood and its music were designated an Intangible Cultural Property of Humanity by UNESCO (2002).

Palos variant: The tambores of the cofradía of St. John the Baptist of Baní, which play the sarandunga music and dance [see chapter 3].

The other main enclave of special music is in Baní (Province of Peravia), a family-based cofradía to St. John the Baptist (see chapter 3 )Its instruments and rhythms are also unique: three small drums (tambores) of double, laced goatskin heads plus one güira. Their rhythms are capitana, jacana, and bomba; holding the drums under the arm, they also play the morano in procession and before the altar.

Dr. Martha Ellen Davis

Archivo General de la Nación (Dominican Republic) & University of Florida (USA)