SUMMARY

1- A Panorama of Dominican Folk Religion and its Music

2- Afro-Dominican Religious Brotherhoods and their Palos Music

3- Case Study of an Afro-Dominican Cofradía: The Brotherhood of St. John the Baptist of Baní and its "Sarandunga"

4- The Dominican Saint's Festival and its Music

5- The Drum Dance [Baile de Palos]

6- Transnational Dominican Palos Music

Musical examples

Sources

6. Transnational Dominican Palos Music

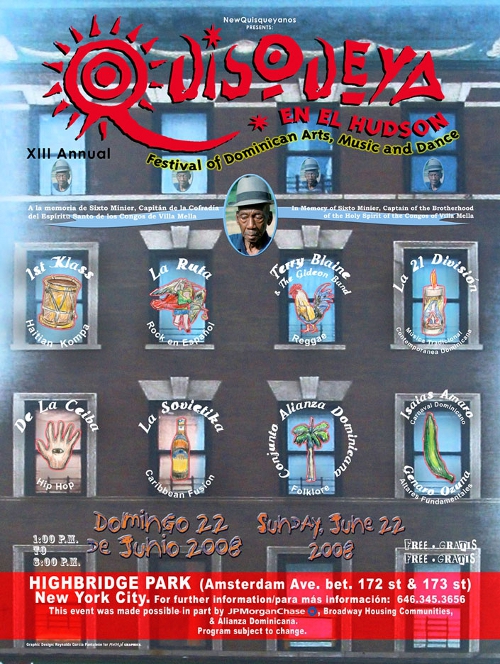

Poster: "Quisqueya en el Hudson" Festival, 2008.

Audio 1 - "Gagá pa' Nueva York" (Edis Sánchez "El Gurú" from CD "El Gran Poder de Dios" of the ensemble Drumayor, 2000)

Uses a Haitian-derived genre and instrumentation.

In addition to Puerto Rico, the main Dominican expatriate community is in New York City, where over a half-million reside. From there, Dominicans have spread north to Providence, Rhode Island; Boston and several northern towns in Massachusetts; and colonies developing elsewhere at present such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The middle- and upper-class sectors tend to be attracted, instead, to Miami and, now, Orlando, Florida. There is also a substantial Dominican presence in various sites of Spain as well as elsewhere in Europe. But it is in New York City, given the sociocultural composition and size of the Dominican community, and secondarily in Boston, that the presence of palos is notable.

New York City is an especially amenable milieu for Afro-Dominican music, for the following reasons: (1) In New York, one is not restricted by race or class; (2) New York is site of intersection of Caribbean and particularly Hispanic-Caribbean and Dominican/Haitian communities, divided down home by geography, politics, and social factors; (3) New York is the artistic capital of the United States and supports the arts; (4) New York has facilitated a Dominican encounter with African-American culture, particularly the “Afrocentric” ideology and jazz music.

Audio 2 - "Vengo de allá" (José Duluc from tape made into CD, "Pánico," 2003)

An arrangement of "Yo soy Ogún Balenyó" from the contemporary oral tradition of vodú festivals of Villa Mella, attributed to Salve singer Enerolisa Núñez; refers to a vodú deity whose counterpart is St. James (Santiago). Expropriated and disseminated for commercial motives by Kinito Méndez, it has become widely popular.

Within this environment, palos started being used in the early 1990s to service vodú public devotional and celebratory rituals ("horas santas", "manís" y “priyés,”). The first commercial ensemble was Claudio Fortunato y sus Guedeses. Claudio, a businessman, learned to drum in New York, apparently in response to a market demand. Other ensembles have followed suit in response to the proliferation of Dominican vodú. The rhythm played is invariably the Salve con palos, based on the habanerarhythm (a misnomer since it was developed in Hispaniola). The same is offered by such ensembles, as another sort of business venture, in night clubs, playing intermezzi with palos. Such activities income for serious musicians as well, as do "artists in the schools" programs.

Among Dominican folk revivalists in New York who are motivated primarily by art or ideology rather than gain, all have in common the fact that they did not learn in situ as part of their own family heritage. Rather, they are largely urban dwellers sincerely interested in their musical heritage as symbolic of their personal and national identity. Revivalists differ from traditional musicians because of their consciousness about the symbolism of the musical folk arts. Therefore, if any authentic folk musicians are present, the revivalists latch onto them as masters. Such was the case in 1994 when the World Music Institute, a non-governmental folk-arts booking agency, under a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, brought master musicians of the congos of Villa Mella and the sarandunga of Baní to rehearse and perform with former rock musician turned revivalist Tony Vicioso and his group, "AsaDifé.” One musician, Roberto Aybar, overstayed his visa and continued as a master sarandungamusician in their midst until his death a decade later.

The revivalists also return to Dominican Republic periodically to commune with the roots of their traditions, joining their local counterparts at specific saints’ festivals as meccas of their national identity. The official Dominican identity for years has been one of "hispanidad," of lauding the Hispanic heritage, racial and cultural, as authentically Dominican, while implying that the black, African, or Haitian presence, taken as synonymous, is inauthentic, indeed invasive. Revivalists’ performance of music of the Afro-Dominican heritage is a form of personal communion with that identity and an affirmation of the legitimacy of the African-derived as national heritage as well. Their recreations of Afro-Dominican music is an educational, proselytizing gesture toward the audience intended to redefine Dominican identity through music.

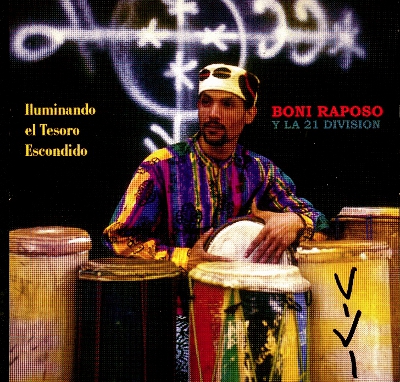

Album cover: Boni Raposo and "La 21 División".

Rehearsal of "Cumbá Carey" (formerly "La 21 División") with "Magic Mejía".

Rehearsal of "Cumbá Carey" with musician/organizer María Terrero.

Such transnational performers include Tony Vicioso as mentioned, the late Boni Raposo, whose former ensemble "La 21 División" has been restructured as "Cumbá-Carey," Osvaldo Sánchez in the U.S. and, in Santo Domingo, his brother, percussionist Edis Sánchez. José Duluc for several years served as a sort of musical ambassador of Afro-Dominican heritage in Japan; in Santo Domingo he has recently founded a new ensemble. "Magic Mejía" directs an excellent group, "Marassá" in Santo Domingo which have been invited to New York, and he himself has gone to rehearse other groups. Irka Mateo's thrust is not Afro-Dominican, rather, with the same sort of fervor, the pursuit and representation of an ignored Native-American heritage and identity. Her first album, produced in New York (2009) is titled "Anacaona," in reference to a Taíno (Native American) legendary political and religious leader vanquished during the earliest years of the conquest.

Poster: "Kalunga" ensemble event featuring folk altars.

Willian [SIC] Alemán, former bassoonist with the Dominican National Symphony, founded the Afro-Dominican ensemble "EcoCumbé" in New York. More recently, he studied sound and video engineering, and founded Latin Mastering Studio in Yonkers, New York, a potentially important venue for Dominican music and musicians. In Santo Domingo, Edis Sánchez has also become a key figure in traditional percussion education at the National Conservatory and folk-arts manager and broker for the Ministry of Culture. In New York, Leonardo Iván Domínguez, although not a musician, has played a very significant role as an educator for young people of Dominican origin at the Alianza Dominicana, a non-profit social-services agency in upper Manhattan. Both Iván and Nina Paulino have served as community organizers for the annual "Quisqueya on the Hudson" festival, an outreach gesture toward Dominican emigrants and the larger public through traditional music. In Santo Domingo, Roldán Marmol, an active although not outstanding performer, is a savvy organizer and fundraiser. His former foundation, Bayahibe, with European monies, produced CDs which joined traditional musicians (such as the Villa Mella singer of creole-style Salves, Enerolisa Núñez) with revivalists. He has recently founded the promising Red de Culturas Locales, or Network of Local Cultures.

Luis Días.

Audio 3 - "Ay, ombe" (Luis Dias from CD, "Jaleo dominicano," ca. 1995)

The revivalist musicians, at home and abroad, draw on the traditional but do not, or do not only, replicate it; rather they tap it for their own creativity. The most outstanding figure here, a truly unique and gifted guitarist and composer, is the late Luis "Terror" Días (d. 2009 at the age of 55). Whether in New York or Santo Domingo, his point of departure was his rural upbringing in Maimón, near Bonao (central-north), where his father played the tres (of the guitar family) and his mother took him to saints' festivals. And he absorbed his soundscape wherever he was, eclectically mixing bits of rhythms, phrases, texts from one palosgenre or another. So he was a creative revivalist, but he was also a Latin rock musician, a master of both acoustic and electric guitars, and composer in both modes. He has been called the father of Dominican rock. He could indeed pontificate very insightfully on cultural history and ideology; but first and foremost Luis Días was a musician. After the rest are gone, his music will live on as the best of a new generation of Dominican music based in part on the palos traditions.

Dr. Martha Ellen Davis

Archivo General de la Nación (Dominican Republic) & University of Florida (USA)