Laméca file

Afro-Colombian music

3. CURRULAO, THE MARIMBA DANCE

Bombo and cununo

There is a very particular set of instruments used in most traditional music in the southern Pacific. One is a large double-headed bass drum called bombo. One of its heads is made of deerskin; the other is made of the skin of a wild boar, and acts as a resonator rather than being directly played. The bombero uses a mallet to play the bombo’s deerskin head, and raps on the wooden shell of the drum with a stick. There may be one or two bombos in a marimba ensemble. The larger, called the bombo golpeador (“striking drum”), marks the beats of each rhythmic cycle, but is also free to improvise and shift between patterns. A more fixed role is ascribed to the smaller bombo arrullador (“lullaby drum”), which mostly interprets a fixed pattern, although the bombero who plays it may adorn that pattern with variations.

Bombo and cununo (fleuve Yurumanguí, 2006).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

There are also two hand drums, called cununos. Although superficially similar to small congas, they are more conical in shape, and are tuned by a system in which wedges hammered into a loop of cable or vine pull on the ring affixing the deerskin head to the body, as are many drums from Cameroon and southern Nigeria. The hole at the bottom of the cununo is tapped with a thin circular piece of wood, rather than remaining open as in drums like the conga, producing a particularly rich timbre. The two cununos of the ensemble include the larger cununo macho, or male cununo, and the smaller cununo hembra, or female. The larger macho usually stays with a basic pattern, while the smaller hembra, with its brighter tone, engages in fills and improvisations, although the two may frequently switch roles.

Cantadoras

A fundamental component in a marimba ensemble are the matronly female singers, called cantadoras. The cantadoras sing a repeated chorus in harmony as another cantadora sings the melody, improvising lyrics and borrowing others from other songs or from popular poetry, and making rhythmic variations and melodic adornments such as an occasional falsetto yodel. As they sing, the cantadoras rhythmically shake a bamboo tube with nails or wooden spikes driven through it, and seeds inside, called guasá.

Cantadoras María Juana Angulo and Carlina Andrade, playing guasás (2005).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

Marimba

Although the cantadoras preside over religious music, the protagonist of the secular dance called currulao is the marimba. The marimba is a large wooden xylophone, with bamboo resonators tuned to each of its keys, which may number anywhere from 14 to 28. The Pacific marimba is derived from prototypes throughout West and Central Africa although, unlike the Central American marimba, it does not retain the use of a membrane on the resonators to produce a buzzing texture.

Pacho and Genaro Torres (Guapi river, 2003).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

The marimba is usually played by two musicians, one who plays a repeated bass part called the bordón, and the other, standing next to him who plays a complex pattern, called the tiple or requinta on the middle and higher-pitched keys, punctuated by variations, adornments, and improvisatory passages called revueltas (from a verb meaning, “stir” or “mix up”). The musician who plays the requinta also sings.

The ability to play the marimba is understood as an esoteric kind of knowledge, and there are many stories about musicians’ making deals with the devil to learn their craft, or even dueling against the devil on the marimba.

Currulao

This marimba music is played during an event called a currulao or “marimba dance”. This is an entirely secular dance context, in which the members of a community gather at the house of the local marimbero, the family members of whom are usually themselves musicians. There, they eat, drink and dance the various genres and songs of the currulao : bambuco, pango, patacoré, berejú, caderona, juga grande (also known as agua larga or agua grande), caramba, torbellino, tolero, maroma, amanecer, tiguarandó, and amadore, and others, each of which has a different set of lyrics and marimba patterns.

Torres family and Pascual Caicedo (Guapi river, 2003).

Photo : Michael Birenbaum Quintero

The dance

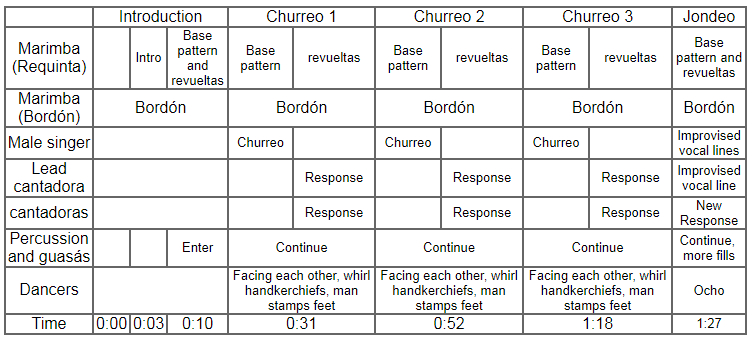

Once the bordonero begins to play, the rest of the ensemble enters and the dancers, male and female, each armed with the indispensable white handkerchief, begin to dance face to face with elegantly upright posture, the men beckoning the women gracefully with their whirling handkerchiefs. The male singer, usually the musician playing the requinta, sings first, emitting a long wordless cry called the churreo, with which the cantadoras harmonize. At the end of the churreo, the marimbero begins an extended improvisatory revuelta, emphasized by fills from the bombos and cununos. The male dancers, each intent on his partner, whirl their handkerchiefs again, and stamp with their bare feet on the wooden floor (zapateos) following the rhythm of the cununo to attract the attention of their partners. He may approach her, opening his arms as if to entrap her, as she twirls and then retreats, if she approaches him, he will do the same.

"Currulao" by Grupo Los Bogas del Pacífico (Teatro Colón, Bogotá, c. 1982)

The cycle of the churreo and intervening revuelta are repeated a few times, after which the music settles into a second section, called the jondeo (related to the word hundir, to sink or to deepen), in which the music intensifies and becomes denser with more protracted improvisations and fills from the instruments. Three separate vocal lines emerge and intertwine: the male singer (glosador) sings long improvised phrases; the lead cantadora improvises a separate line in a complicated rhythmic and harmonic counterpoint between and against the vocal lines of the glosador; and the rest of the cantadoras, called respondedoras (responders) or bajoneras (related to the word baja, or low, presumably referring to their harmonized voices which may rest on a note an octave below that of the solista) repeat a harmonized stanza as an ostinato.

The dancers change their steps, traveling in a circle facing one another, close enough to touch but never touching, and punctuating their circling with spins, the zapateos of the man, and expressive loops and twirls of the handkerchief. The piece is followed by another, and another; a currulao usually last until dawn and often for three or more days straight.

“Adios Guapi” by Grupo Naidy

Adapted from Tascón (2008). This chart accompanies the previous musical example.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. Black Colombia

2. The Southern Pacific

3. Currulao, the marimba dance

4. Arrullo, a lullaby for the Saints

5. Alabados and Chigualo, music for the dead

6. Black Pacific modernities

Musical illustrations

Sources

______________________________________

by Dr Michael Birenbaum Quintero

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Général de la Guadeloupe, 2009-2016