Laméca file

Cuban Abakuá music

4. ABAKUÁ INFLUENCE IN CUBAN POPULAR MUSIC

Partially inspired by the Harlem Renaissance and “Bohemian” Paris of the 1920s and 1930s, the intellectual and artistic movement called Afrocubanismo emerged in Havana during this same period. Seeking to define a national culture, the movement drew inspiration from local black and mulatto working-class cultures. Because the Abakuá were anticolonial, endemic to Cuba, highly organized, exclusively male, secret, and uniquely costumed, they became an important symbol for the Afrocubanistas.

At the forefront of this movement were Fernando Ortiz (1881-1969), who in 1923 founded the Sociedad de Folklore Cubano; Nicolás Guillén (1902-1989), who published his first book of poetry Motivos de son, in 1930; Alejo Carpentier (1904-1980), who published his first novel, ¡Ecue-Yamba-O!, using an Abakuá theme, in 1933; and Lydia Cabrera (1900-1991), who published Contes Nègres de Cuba, in 1936. The composer Ernesto Lecuona (1895-1963) used Abakuá themes in his 1930 composition “Danza de los náñigos [Abakuá]”; the singer Rita Montaner performed Félix Caignet’s composition “Carabalí” in Paris in the late 1920s. Symphonic composers Amadeo Roldán and Alejandro Caturla explored using Abakuá and other Afro-Cuban themes for the creation of a ‘national’ symphonic music, following the example of Bella Bartok. In 1931, Amadeo Roldán premiered Yamba-O, by Caturla, with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Cuba in the National Theater. In 1932, “Elegía del Enkiko” [Elegy of the rooster] by Caturla was sung in the War Memorial of New York. Both works were composed on Abakuá themes (Caturla 2007: 262, 264). This trend continued sporadically throughout the twentieth century (Irakere with Cuba’s National Symphonic Orchestra 1983).

Cuba’s renowned painter Wifredo Lam (1902-1982) returned from an apprenticeship with Pablo Picasso in France to live in Cuba from 1941 to 1952, where Alejo Carpentier and Lydia Cabrera encouraged his exploration of African-derived themes. A 1943 painting (untitled) depicts an Abakuá Íreme with conical headgear and playing a drum. The conical Abakuá mask appears repeatedly in Lam’s later work in abstracted forms. In 1947 he painted “Cuarto Fambá,” his imaginary recreation of the Abakuá initiation room, which of course he never saw.

Many important musicians of Cuban popular music have been Abakuá members. Miguel Failde, credited as the creator of the Danzón genre in Matanzas in the 1870s, used Abakuá theme in his compositions.

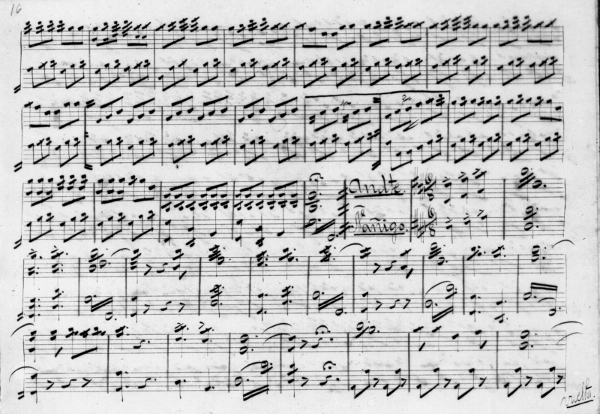

Page from a composition by Failde, with an “Andante Ñáñigo” section (Ñáñigo being a reference to Abakuá). From the late 19th century.

Thanks to Zoila Lapique. Archives of the Mueso de Música, Havana

Because the rumba percussion ensembles were marginalized and rarely recorded before the 1950s, many early composers and compositions remain obscure. Ignacio Piñeiro (1888-1969), a member of the Abakuá group Efóri Komó, founded the son group Septeto Nacional in 1927 through which he created the modern son by fusing it with rumba styles in the montuno section. Piñeiro was known as “the poet of the son” because his over 400 compositions helped create the global son craze of the 1930s.

All the major rumba groups of Havana and Matanzas were formed by Abakuá members: Ignacio Piñeiro; A. Zayas, Guaguancó Matancero (Los Muñequitos de Matanzas), Los Papines, Yoruba Andabo, etc.) and recorded Abakuá music with chants. Since the first recordings of Cuban music in the early 20th century, rumba has consistently been the fundamental reference for Cuban popular music. That is, phrases created in the inspirations and choruses of rumba performances were commonly referenced by composers of popular dance music that were recorded by RCA, Victor and other companies.

Chano Pozo (1915-1948), a member of the group Munyánga Efó, composed the classic “Blen, blen, blen” in 1940. Upon migration to New York City in 1947, he recorded the Abakuá ceremonial “Abasí.” His compositions and performances with jazz great Dizzy Gillespie in the late 1940s helped create the bebop genre, and are celebrated as a foundation to Latin jazz. Pozo and Gillespie collaborated on compositions in Afro-Cuban jazz (or Latin jazz), including “Manteca” and “Afro-Cuban Suite,” performed in 1947 with the Gillespie Band, integrating Abakuá ceremonial music and chants with jazz harmonies. In “Afro-Cuban Suite,” Pozo chants “Jeyey baribá benkamá,” a ritual phrase in homage to the celestial bodies. Dizzy performed these compositions into the mid-1980s as standards, fusing Abakuá rhythms to popular music in the USA.

The enduring legacy of Pozo-Gillespie collaboration is felt in numerous ways. In the late 1940s conga and bongó drums became symbols for the emerging Beatnik movement, and the conga drum is now a standard instrument in the United States. Musical tributes to Chano Pozo began in 1949, the year after his death, and continue in the twenty-first century. In Cuba, recordings of Irakere, an important jazz group, used Abakuá themes in the 1970-1980s, most famously “Iya,” a reference to the Fish Tánse.

Other Cuban music greats in New York City, although not Abakuá members, were from Havana barrios with Abakuá traditions; they referenced these consistently in their compositions. For example, among the earliest recordings of Afro-Cuban Jazz in the 1940s, “Tanga”, by Mario Bauza’s, became the theme for Machito’s Big Band, Tanga is based upon the Abakuá term “Batanga”. One recording has Machito uttering the Abakuá phrase: “tíe, tíe, tíe,” used by the Moruá to guide an Íreme on the patio during ceremonies.

In the 1950s, Abakuá musician Julito Collazo arrived to New York City to join Katherine Dunham’s performance troupe. He joined other musicians like Mongo Santamaría to record many important tracks with Abakuá content and jazz arrangements. The production is continued into the present by the Ecobio Enyenisón project (2009), and its participating Abakuá musicians in New York City, as discussed in the first section of this essay.

______________________________________

SUMMARY

1. The Abakuá institution : a Carabalí foundation in Cuban society

2. Styles of Abakuá music : Nyánkue rites; Efó and Efí lineages; the lamellophone; percussion instruments

3. Abakuá ceremonial music

4. Abakuá influence in Cuban popular music

Musical examples

Glossary

Sources

______________________________________

By Dr Ivor L. Miller

© Médiathèque Caraïbe / Conseil Départemental de la Guadeloupe, 2016